Listen:

Check out all episodes on the My Favorite Mistake main page.

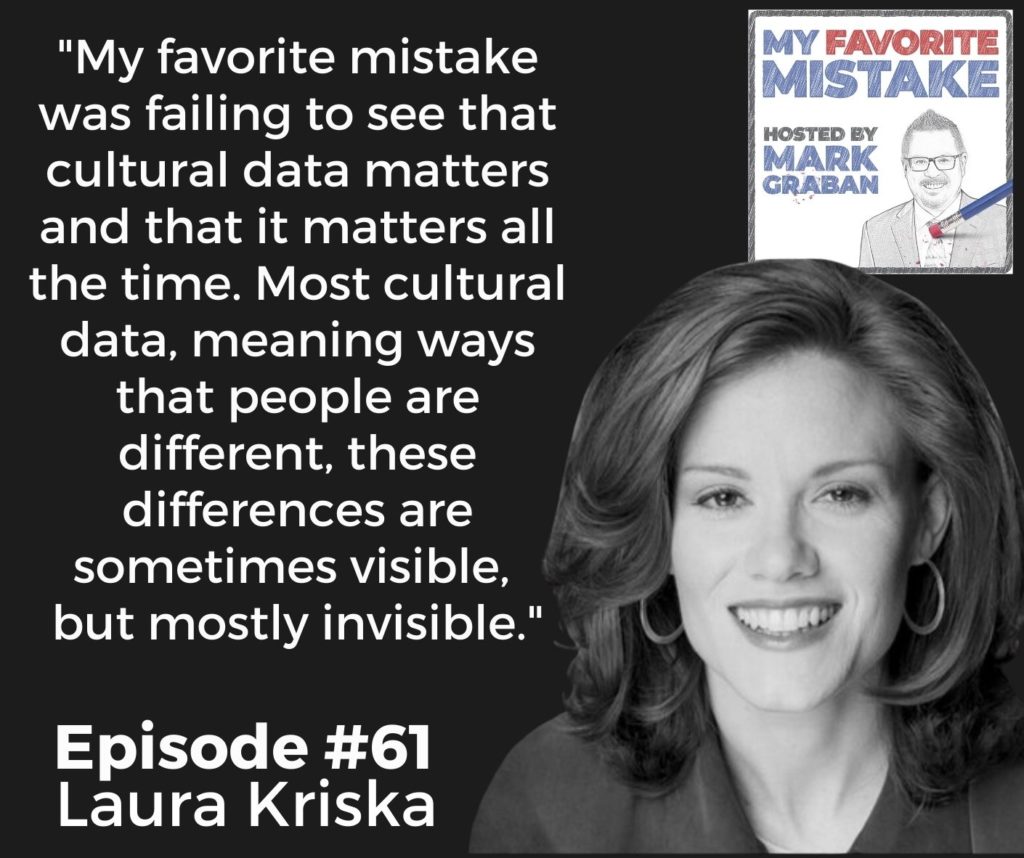

My guest for Episode #61 is Laura Kriska. When she was just 22, Laura became the first American woman to work in the Tokyo headquarters of Honda Motor Company.

Her experience working with thousands of middle-aged Japanese men inspired her to write her first book The Accidental Office Lady: An American Woman in Corporate Japan.

Inspired to create a ‘WE building’ revolution, Laura wrote her latest book The Business of We: The Proven Three-Step Process for Closing the Gap Between Us and Them in Your Workplace – a new approach to diversity, cultural difference, and inclusion that will increase employee retention and productivity and prevent misunderstandings that lead to lost revenue, lost time and increased legal risk.

In today's episode, Laura and host Mark Graban talk about her experiences working Japan and what she has learned about working across cultural and organizational divides.

Laura also discusses topics including:

- How her mistake could have been avoided with one sentence

- Failing to see how “cultural data” matters – the ways people are different

- Why did she offend the “most important office lady”?

- A “quality circle” project about getting rid of the women's uniforms

- What do you mean by a “we” culture?

- What's the connection between “we” and the Japanese word “wa” (harmony)

- Is a “we culture”? more prevalent in Japan and other Eastern cultures?

- What does she mean by being on “the home team” in a country or a culture?

- Paul O'Neill as a “we builder”

- Her article: “Covid-19 is not killing us, polarization is“

Here is Laura at work on her first day:

And a short video clip:

Scroll down to find:

- Video player

- Quotes

- How to subscribe

- Full transcript

You can listen to or watch the episode below. A transcript also follows lower on this page. Please subscribe, rate, and review via Apple Podcasts or Podchaser! You can now sign up to get new episodes via email, to make sure you don't miss an episode. This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network.

Watch:

Quotes:

!["My favorite mistake [on my first day working for Honda in Japan] could have been avoided with

one sentence."](https://www.markgraban.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Laura-Kriska-My-Favorite-Mistake-2-1024x858.jpg)

!["I had this knowledge that other women didn't like the uniform. So I started a [quality] circle [group], to abolish [the blue polyester] women's uniforms."](https://www.markgraban.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Laura-Kriska-My-Favorite-Mistake-4-1024x858.jpg)

Subscribe, Follow, Support, Rate, and Review!

Please subscribe, rate, and review the podcast — that helps others find this content and you'll be sure to get future episodes as they are released weekly. You can also become a financial supporter of the show through Anchor.fm.

Other Ways to Subscribe — Apps & Email

Automated Transcript (Likely Contains Mistakes)

Mark Graban (1s):

Episode 61, Laura Kriska, author of “The Business of We.”

Laura Kriska (7s):

My favorite mistake could have been avoided with one sentence.

Mark Graban (16s):

I'm Mark Graban. This is my favorite mistake. In this podcast you'll hear business leaders and other really interesting people talking about their favorite mistakes, because we all make mistakes, but what matters is learning from our mistakes instead of repeating them over and over again. So this is the place for honest reflection and conversation, personal growth and professional success. Visit our website at myfavoritemistakepodcast.com for show notes, links, and more information. You can go to MarkGraban.com/mistake61, please subscribe, rate, and review. And now on with the show, our guest today is Laura Kriska.

Mark Graban (59s):

She describes herself as a cross-cultural consultant and author. I'll tell you a little bit about her, but first off, Laura, thank you for being here on the podcast. How are you?

Laura Kriska (1m 9s):

Oh, thanks Mark. I'm really glad to be here.

Mark Graban (1m 12s):

So Laura has a really interesting background when she was just 22. She was the first American woman to work in the Tokyo headquarters of Honda Motor Company and her experience working there with thousands of middle-aged Japanese men inspired her to write her first book, “The Accidental Office Lady,” and then she has she's written. Her latest book is called “The Business of We,” and we'll have a chance to talk about all of that today. How do we have an approach to diversity and cultural building bridges across cultural differences and being more inclusive in a way that increases employee retention and productivity and is just good.

Mark Graban (1m 52s):

It sounds like maybe it's just first question is, yeah, this is good for the people involved and for the organizations, when we take an approach like that?

Laura Kriska (2m 1s):

It is good.

Mark Graban (2m 3s):

I asked a closed ended question. That was a mistake on my part. That was really bad interviewing, but we'll talk more about the book, please. Forgive my mistake, Laura. No problem. I put you in a bad position there, but I'm going to ask an open-ended question here to really, to get things off to a better start. Laura, looking back at your experiences, what would you say is your favorite mistake?

Laura Kriska (2m 28s):

My favorite mistake caused me a year of heartache confusion and unhappiness. My favorite mistake could have been avoided with one sentence. And my favorite mistake has informed my entire 30 year career and is the basis of the book. I just wrote The Business of We.

Mark Graban (2m 56s):

Wow. So you're teeing that up. Well, can you tell us happened?

Laura Kriska (3m 1s):

My favorite mistake was failing to see that cultural data matters and that it matters all the time and that most of cultural data, meaning ways that people are different, different norms of behavior, that these differences are sometimes visible, but mostly invisible. So let me tell you what happened. I was 22. I'm in Tokyo at the door of Honda Motor Company. I am so excited to be starting my very first professional job. I look like a professional woman I have on this cream colored suit.

Laura Kriska (3m 45s):

I have an empty briefcase that matches, but it's, you know, a matching briefcase. And I go to my job. There's a little detour where I am asked to wear a polyester blue uniform. That's only for women, which I do because I am flexible and I can adjust to cultural norms. This is how I thought of myself. I had a lot of experience in Japan before I even got there. So I thought I knew what I was getting into. And I am introduced to the group of 10 Japanese women that I'm going to be working with for a year. We were the executive secretary and we served the 40 directors of Honda Motor Company.

Laura Kriska (4m 29s):

And within hours I offended the most important office lady without realizing it. And I did that because I failed to recognize that she was a senior person. I couldn't see that she was senior because there were no visible indicators that she was senior. We all wore the same blue uniform. We sat at the same white desks. We did the same job, serving tea and cleaning ashtrays. That's another story.

Mark Graban (5m 6s):

Well, the ashtrays, in Japan, there's still a lot of smoking in Japan now, but yes,

Laura Kriska (5m 10s):

At the time there was, it was welcome in the office. And I treated her as I was taught and to being in a professional environment, which was to be polite and respectful, but I failed to show deference. I don't know if you've ever done martial arts, but I had practiced a martial art and there in martial arts, there were two groups of people. There are black belts and there are white belts. And in a dojo, white belts show deference. They get there early, they clean up the mats, they wash the stuff there. You know, they get beat up by the black belts.

Laura Kriska (5m 50s):

That's how it works. And even though I had that experience in a dojo, I failed to understand how important is in a Japanese workplace. Because in America, there is a, a narrative that's very strong and important that we learn growing up, which is treat everybody the same equally. We don't treat people differently because of what they look like or where they come from. And so my method of starting a relationship, right? This is something everyone in business needs to do is start good professional relationships. So I treated her the same and that was my mistake.

Mark Graban (6m 36s):

Wow. Now you said it could have been avoided by one sentence. What, what was that sentence or what was the opportunity to use it?

Laura Kriska (6m 44s):

So it took me a while to understand that this hierarchy mattered in that I started to understand how people show deference and it's not just Japan. There are many organizations or countries, you know, any country with a king or a queen Thailand, England, you know, there are lots of countries that pay attention to these kinds of things. And, and United States is one that really doesn't. And I recognized how, if I had simply used the following sentence. So, so, you know, when I would ask her things, I would just say like, I would say to you, Oh Mark, could you tell me where we keep the pens? Or where is the tea or something? And it was very egalitarian and it was polite, but it was egalitarian.

Laura Kriska (7m 29s):

And the one sentence, if I could go back in time, I would have used, is this, I'm sorry to bother you, Mark. Could I ask you a few questions right now? Right. A little bit of deference, acknowledging her years of service, her experience, her skill. And it never occurred to me because I wasn't looking for invisible cultural difference. And I thought I understood it.

Mark Graban (7m 58s):

Now, what you described there in that, that sentence basically. Can, can I ask you some questions? You know, that's not over the top, like a brown nosing or kissing up, but I guess just that, that act of respect of asking the question of, can I ask you questions instead of just jumping in and away that might've seemed demanding.

Laura Kriska (8m 20s):

I assumed in equal status with her that didn't exist. And from her point of view and it was true. I had no experience. I was operating in a foreign country in a foreign language and a job she could do backward and forward. And I'm completely comfortable showing deference to people who know more than I do and, and understand things and have worked longer and harder. It, but it's just not something I recognized as important in that situation. And that's what I mean, that cultural data matters all the time. And when we traveled to another country, it's more, it's easier to see this and we can be prepared for it, but cultural data matters everywhere all the time.

Laura Kriska (9m 6s):

Even with people who you think you're in alignment with.

Mark Graban (9m 11s):

Yeah. So you talk about, there's a couple of things about the story. Maybe we ask you to elaborate on you talk about this uniform that you were given the blue polyester uniform the times when I've been to Japan and you're on the train and you see commuters, whether it's men or women, you see black suit, black suit, black suit men and women, black suit, maybe dark gray. But I don't like there's there's, there is like very much a business uniform, a lot of ties. And, and so I'm, I'm, I'm curious, did, did even that light colored business suit sort of stand out in a way that is maybe uncomfortable in Japanese culture, you're there, you're there, you're already standing out as an, as an American.

Laura Kriska (10m 4s):

I might as well have not. I should have just shown up in jeans because my business clothes were not welcome at what wasn't appropriate for that at the time. And in actually, there's a kind of interesting story of, I finally challenged that, that rule after two years of working in Japan, and this was based on this idea that I talk about in my book, which is us versus them. And I was very much other than them when I showed up in Japan, even though I wanted to be there, you know, the way I spoke Japanese, the way I looked, the way I dressed, you know, I was outside the norms and the home team in that case, the home team is whatever group is in the dominant position was middle-aged Japanese men.

Laura Kriska (10m 53s):

And so from the beginning I felt I was, I had a marginalized voice. I was an outsider. And, and so I had to work to kind of fit in and the uniform was a part of that. So I just really hadn't prepared as well as I should have.

Mark Graban (11m 17s):

Well, I was about to ask you, when you say preparation, what did the company do to help prepare you as an outsider to Japanese culture? And I saw from one of your videos, you were born in Japan, but not really raised there. Can you, can you tell us more about that? A little bit more about your background and then to the question of, you know, did the company sets you up for success or not in terms of cultural norms and expectations?

Laura Kriska (11m 45s):

Well, I, I grew up in Columbus, Ohio from the age of two, so I have no memories of Japan, but my parents love Japan. I love Japan. So when I was a college student, I got the chance to spend my junior year at University in Tokyo, which was great. And so having that level of familiarity gave me the sense that I knew everything. Now, remember I was 22, most 22 year olds think they know everything. So some of that was just my generation and the company. I, they tried to prepare me. I think the company also didn't know what they were doing.

Laura Kriska (12m 26s):

They had great intentions. They were trying to internationalize, but Japan is a country at the time that was 99% Japanese. Now it's 98%, not Japanese people. So there is a lot of homogeneity, like you mentioned your observations on the trains and seeing how people tend to dress alike, et cetera. So I had to figure out a lot of this on my own. And this is part of the reason I wrote my first book, the accidental office lady was to share the lessons that were kind of hard, one for me and, and trying to share those with other professionals because when we figure out the us versus them dynamics, when we can narrow the gaps, instead of spending our time feeling unhappy and confused and, you know, having poor communication and ineffective teamwork, we actually can use our time and our skills and our talents toward innovation and great results, et cetera.

Laura Kriska (13m 25s):

And that's the premise of the new book, which is how to identify us versus them dynamics. And then how to address the ones that are most damaging in any organization.

Mark Graban (13m 37s):

Yeah. So the, the book title again is The Business of We and Laura, you, you talked about how this formative mistake, this experience that you made, helped spark a career's worth of interest. So what, what were some of, what were some of those experiences then that you had even at Honda, in Japan of starting to break down us versus them into, into way.

Laura Kriska (14m 6s):

So I worked with the group of 10 Japanese office ladies. We had the same jobs and I was the youngest member of the group. And I got to know them over time, all the office ladies. And there were two in particular who I just really bonded with. I was eager to make connections. I, you know, I was alone. I was single. I was very open to building meaningful relationships, even outside of work. So there were two women in particular, we would have lunch together. We got to know each other. We started hanging out on the weekends. We started traveling together. So these became my people and that narrowed the gap for me personally, in the workplace, because I could then go to them.

Laura Kriska (14m 50s):

I, they were my allies. I could help them with things that related to English language or other things. And, but we became real friends. And so through the process of becoming real friends, we develop trust. I learned lots of things. You know, it took me time. And one of the things that I learned was that they didn't like the uniforms. I was, I was so surprised. I had made assumptions as we all do that since no one complained. And they wore the uniforms. This was a policy that had been in place for years and years. You know, hundreds of women in this headquarter office wearing uniform, I was surprised, but it was the process of face to face interactions of increasing depth that led to the building of trust.

Laura Kriska (15m 41s):

That then led to me learning this piece of information. And then the company sponsored an annual quality circle. This is a familiar phrase, a phrase to you. I know. And they, they called it NH Circle, New Honda circle. And you know, it's a mechanism of change and they invite all employees, Hey, participate in this. Year's, you know, new ideas, circle ideas, et cetera. So I had this knowledge that other women didn't like the uniform. So I started a circle, a quality circle to abolish women's uniforms, And I recruited other members.

Mark Graban (16m 25s):

Yeah. Did that seem risky or did you feel like, okay, no, they're there. They're asking for this input, I'm going to give it,

Laura Kriska (16m 32s):

It did not feel risky. It was exactly what they were asking for. And I stayed exactly within the parameters that they requested. And Honda is a company that is genuinely interested in innovations that will improve things. Usually it has to do with improving safety, saving costs, increasing production, as you know. And so this was a little bit outside of that. I remember feeling encouraged when I saw another circle's idea, which was about smoking and it was about limiting smoking. So it was a behavioral norm that they were trying to change. And I was trying to change this somewhat of a behavioral rule.

Laura Kriska (17m 14s):

And I pulled together a group. There were, there were no Japanese men. I couldn't get any Japanese men involved, but several Japanese women, there's a French guy, an American guy. And we started the process as a quality circle is done, where you, you research, you study and we really dug into it. What are other companies doing? How much does this cost? The company? We, in fact, discovered that the women's locker room was taking up quite a bit of so much space in the, in the building, in Alabama, in Tokyo, that we leasing office space in a building next door. So, you know, accumulating.

Laura Kriska (17m 55s):

And then we did polls. We surveyed women. I remember that was, felt a little risky asking the women to, you know, fill out this is all paper right back then and asking for their opinions. And when we, you know, it, it took a long time. We propose this. We, we did the process and because we weren't really able to prove our outcomes, which is normally necessary as you well know, it was more of an imagined success. And the company decided to take our idea and they transferred it outside of the circle system. After the first or second rounds of that kind of friendly competition and a different department, then studied it.

Laura Kriska (18m 41s):

Now, I was really excited. I was like, look what we've done. You know, in the matter of a few weeks we have put together and then it went nowhere.

Mark Graban (18m 52s):

I don't know. So it was moving it out a way of sort of politely killing the project.

Laura Kriska (18m 59s):

Well, that's what I thought. And I would check in every once in a while and the leader of the group would say, can those Seamus, we are studying this. We are researching this. And I frankly kind of gave up. But then about, I dunno, a few weeks before I was to leave Japan, I had been working there for two and a half years. And the study group had had this idea for, I think, close to a year. Suddenly there was an announcement starting Monday, women's uniforms will be optional.

Mark Graban (19m 38s):

We couldn't believe

Laura Kriska (19m 39s):

We all gathered the whole team gathered. And we, you know, we learned that they had in fact then in very kind of process oriented, lean fashion for hats followed every step studied, you know, the lease next door, the cost opinions. And they had come to the conclusion that the uniforms should in fact be optional.

Mark Graban (20m 3s):

Yeah. Well, I was wondering, cause you know, with that, with that story, Y I've been to Japan five times on business learning tours and the orientation we've received about these trips, you know, talks about the cultural norms of maintaining harmony and where that sometimes between hierarchy seniority, maintaining harmony sometimes makes it difficult for people to speak up with improvement ideas. And yeah, I was told stories about like this hesitancy to say no. So the story, the one story I remember, I'm curious, your thoughts or reflections on this light.

Mark Graban (20m 43s):

If you were to go and try to buy tickets for a play and the play sold out the, the, the person at the ticket counter, wouldn't say, no, you can't buy a ticket, but they might turn and pretend to be looking through a box and looking for tickets and that eventually you should get the hint that, well, I guess there are no tickets and I'm, I'm, I'm going to leave or phrases like, well, it would be difficult. Yes. Yes. So that's what I thought you were getting with this product. Like, can we get rid of the uniforms? Well, it would be difficult. We are researching it.

Laura Kriska (21m 16s):

I, I too thought that, but in fact it was this other cultural issue that took priority, which was being thorough and being careful. If you're going to change a corporate rule that has been in effect for 30 years, let's make sure we're doing it correctly. And I'm happy to report to you that new rule is in effect and has been in effect for now over about 30 years.

Mark Graban (21m 40s):

That's cool. Let me talk about, you know, the word harmony and, you know, fitting in. So I think that goes to the uniformity of business suits. Nobody talks on the train, nobody eats, there are certain cultural norms that are just so accepted, no jaywalking of like, you know, if you see, I, I, you know, it would be really rare to see a Japanese person crossing against the light or jaywalking and these violations of norms become really visible. It seems. And, and so it was emphasized like, as you know, as a white visitor, you're already disturbing harmony just by, by being there, you can try to do your best to, to fit in and behave, but you're still disturbing harmony, but of these different words like law and, and, and as a word for harmony, it's, it's interesting that Y in, we were only one letter off, I don't know if that's coincidence or not.

Laura Kriska (22m 38s):

I want to say it's not, but it is. That's great. I haven't ever thought of that. Look at you. Huh. That's good.

Mark Graban (22m 50s):

But, but, but there is this real Japanese sense of, and as much as you can generalize about Eastern cultures, more of a weak group oriented society where, you know, here in the, in the United States and a lot of time, a lot of cases, it's every person for themselves. And unfortunately some of that now comes out through the pandemic. So there's kind of like a broad, I guess, a broad question there, but maybe bringing it back to your work with American companies. Like what success have you seen? I'm not saying we're hopeless in terms of rallying around a goal or focusing on we like successful companies really seem to do that.

Mark Graban (23m 30s):

So that was kind of a very broad, rambling combination of statement and question, what do you think?

Laura Kriska (23m 36s):

I would say that there are two things that I really learned from Japan and one of them is good and one's positive and one's negative. And the positive one is, is what you just said. There is a really strong sense of the common good in Japan. It's taught from a very young age and that this is not because Japanese people have a magical ability it's that they are, they're taught this it's modeled equity in terms of earned income is modeled. You know, you don't get the huge gaps in payment in Japan that you see in America. And, you know, that certainly leads to huge us versus them dynamic.

Laura Kriska (24m 17s):

So, you know, when the, the CEO is making 300, 400, 500 times the average employee, well, good luck with creating a we culture.

Mark Graban (24m 27s):

Sure. And that gap keeps expanding and the gap is yes, it's, the gap is much smaller

Laura Kriska (24m 33s):

Japan. And so that idea of a common good working toward the common good. I, I like that. I think there are times when that's really important and the COVID epidemic has shown evidence of how working together toward the same goal with certain norms that are in agreement works. Japan has had fewer than 2000 deaths of COVID 19, where America's over now 500,000, because we have allowed a culture of us versus them to exist over proven practices and norms that keep everyone safe. So this should not be an us versus them mask or no mask.

Laura Kriska (25m 16s):

It should be. It's simple tug of war, humans versus virus. That's the only us versus them that is actually at play here. So countries like Japan who were able to pull together, get behind leadership, having leadership, talk about us, you know, us, we humans versus the virus have been more successful. So there absolutely is a important place for behaving in a more common way. And Japanese culture, Japanese people tend to be really good at that. So I admire that. And I've learned from that.

Laura Kriska (25m 57s):

It has informed my work, the part that does not or help help me see where us and them dynamics can be difficult is when I worked with Japanese ex-pats ex-patriots and wrote, we call them rotational staff sometimes when they would leave Japan and go work in Paris or London or Sao Paulo. And because of their lack of familiarity with the local culture, maybe hiding behind language concerns, they would often not integrate with the local culture. And they just hung out with each other.

Laura Kriska (26m 39s):

They made all the decisions. They had all the positions of power and they would fail to take into consideration data from people in the local environments. And this made them less competitive. It caused human relations complaints and even legal problems in some cases. And so I, I spent my career helping that dynamic to be less damaging, to help those very hardworking, talented, deeply loyal professionals learn to integrate more successfully with people who didn't look like them, who didn't sound like them, who didn't pray like them, who were just, you know, they were different and doing that for so many years.

Laura Kriska (27m 26s):

I noticed another parallel Mark, which is right here in the United States. We like to say, Oh, we're so diverse. And certainly our demographics, our show that we are diverse, but we are pretty segregated when it comes to the top levels of corporate America. And what I recognized was the, the homogeneity of Japan was duplicated and the top levels of corporate America. And so instead of middle-aged Japanese men, it's, middle-aged white men. And I always like to make a disclaimer. I am not against middle-aged white men. I'm married to one and I've created two future white men for the planet.

Mark Graban (28m 5s):

Yeah. And as a, as a middle-aged white man, I take no offense. I, I see what, what, what you're getting at. Yeah. Cause there, there is that you were an outsider trying to fit in to the dominant Japanese culture. When I've talked with black friends and colleagues, they talk about the struggle of fitting into, I mean, no offense. What is the dominant white culture in workplaces and, and America. And when you are part of the homogeneous group, that's, that's dominant it's it's eye-opening to hear the things that I take for granted. So I've come to understand the word privilege I have, that I can't be denied.

Mark Graban (28m 50s):

I can try to deal with it and I can try to use it to elevate others, but the privilege doesn't go away. At least not in the short term, even if we're working toward that,

Laura Kriska (29m 0s):

I like to refer to this in the book, I call it the home team because what does a home team have an advantage? Right? So the, the, every organization has a home team, different departments. I have a friend who works in a huge company and in her department, she's a middle-aged white woman. There are many Chinese speaking women. And so the dominant, the home team in that department is Chinese speaking middle-aged women. So the idea of a home team can apply to many situations just as us versus them can apply to many situations and incumbent upon those of us on a particular home team to see it recognize the advantages, just like you said, and then take action.

Laura Kriska (29m 51s):

This is, we building is taking action to actively narrow a gap between you and somebody who does not identify with that home team.

Mark Graban (30m 2s):

Yeah. So the closest, I'm sorry, I'm thinking of the situation. And I haven't been greatly disadvantaged in any of the situations, but sometimes it's almost funny where in the work I do with hospitals, the home team is let's say nurses and they're all women. And so I'm the only man and the only engineer, the only non-nurse in a meeting or in a room that does sometimes give me pause. But again, like there's no great harm or discrimination. That's, that's come to me. But, but it's eye opening to think of, of what it's like to be the only one in the room as someone of my black friends and colleagues will articulate being in that situation all the time,

Laura Kriska (30m 43s):

Every day. So I often ask people, when have you felt like of them and you, you just shared an example of when you're in this room and I put being a them, I don't think they're all equal. I put them in three categories, there are inconsequential experiences, consequential experiences and game changing and game changing is when you feel like of them every single day. And usually it's based on something about your appearance that people immediately identify and then react to them.

Mark Graban (31m 17s):

Sure. And, and mine was like I said, no harm, sometimes our misunderstanding or what happened. One other thing though, when you talk about us versus them, you know, I started my career, not at Honda, but in general motors in Michigan, 1995, my goodness us versus them was at the core of general motors and the United auto workers. And there were efforts to try to turn that like the, the first man, the first plant manager I worked under was a total us versus them. Then I have a second plant manager who had experienced as being trained by Toyota in California. He was trying to create a weak culture and it was difficult and there was progress being made.

Mark Graban (32m 2s):

And the one parallel that comes to mind and I'll link to this in the show notes, Laura wrote a very nice article in CEO World magazine saying COVID-19 is not killing us — Polarization is. And the thought that comes to mind thinking back to the Detroit automakers, I would say at the, you know, at the time it was not the Japanese auto makers that were killing them. It was polarization that culture within the automakers was so toxic and so dysfunctional. And I do not believe the union for that long story short.

Laura Kriska (32m 34s):

And I think it w my cursory understanding of GM, Chrysler and you know, how those organizations operated, they play so many, there were so many indicators of us versus them and divisions, you know, executive cafeterias selected parking, lots, huge salaries, what you were at. And if you look at places like Toyota and Honda, we, I know from Honda's my own experience, they took practical choice. They made practical choices to limit those things. So for example, there was no executive dining room, literally like everybody ate in the same cafeteria, you ate the same food.

Laura Kriska (33m 16s):

We wore the same white coveralls with our name and a red patch. There were not special parking lots. The salary differentiation was not as huge. And those are meaningful. Those strategies are meaningful and create much more of a feeling of we. And those are the things I really admire.

Mark Graban (33m 40s):

In some hospitals, you still have special dining room for the physicians. You have a physician's lounge that has I'm remember one case, much bigger, nicer TV than the break room for the nurses and other staff. And it's unfortunate when there's us versus them because the we mentality in healthcare should be completely oriented around the patient and their care and us versus them distracts from that.

Laura Kriska (34m 6s):

Absolutely. W why are there different lounges for physicians and nurses

Mark Graban (34m 15s):

Tradition, hierarchy power, because we can, I, you know, the so-and-so dynamic of sometimes, you know, the, the physicians or surgeons is seen or seen as people who bring revenue into the hospital in American healthcare. They're not employees. They have choice of like, well, so we're going to cater to them. They're not quote unquote, stuck here. And you'd hate to think, you know, your, your basis of anything is that my nurses or whoever are stuck here, you should be competing for their loyalty every day.

Laura Kriska (34m 46s):

It reminds me, sorry to interrupt you. Yeah. It reminds me exactly of organizations where, you know, you have sales and marketing and accounting, you know, all these different departments. And there is that hierarchical money, earning departments versus money using departments. And when the leadership goes along with that narrative in prioritizes, the so-called moneymakers, that's a bad choice that is leading to us versus them dynamics that undermine the entire competitiveness of the organization. And when you point out to a very successful sales person, you know, you can't really do this well without the accounting department and the, the marketing staff and, and the lawyer who's doing, you know, and there's this idea that people in accounting or whatever are interchangeable, and it's just so false.

Laura Kriska (35m 41s):

And certainly there is a role for compensating people differently based on their education skills and experience and performance. But if you have such a divided attitude toward your own team, you are undermining, undermining the overall competitiveness.

Mark Graban (36m 0s):

And one example, I think of, of an executive, I admire a lot who created a weak culture, was Paul O'Neill who passed away about a year ago. He was CEO of Alcoa in Pittsburgh. And there are great videos online of him touring media through this new headquarters that they built, where everybody, including Mr. O'Neill was in a cubicle. And I call him Mr. O'Neill out of deference. He would be quick to say, call me Paul. And he got rid of when he became CEO. There, there are stories that we've been able to share. He got rid of the executive dining room and these different parks and started challenging, like the idea that you're an executive and you show up and you get free orange juice and Danish every morning.

Mark Graban (36m 46s):

And he's like, we pay you well, you can afford that. Right. Do we do we, do we offer that to every employee? And he got rid a lot of those. He got rid of a lot of those trappings of privilege and hierarchy in, in many ways. And, and one that I admire him for, he got rid of the company country club membership because the country club was not diverse. And this was in, I think the late eighties…

Laura Kriska (37m 12s):

I like that…

Mark Graban (37m 13s):

I think Paul O'Neill was, was a, we,

Laura Kriska (37m 19s):

I would call him a, we builder. We builders. I mean, this is what I, I am. My life's mission is to inspire a, we building revolution and I can't do it by myself. I need your help. And all of your listeners help. And in calling out, we builders is a great example, and anybody can be a wee builder. You don't have to be the CEO. You know, we building and being a, we builder means identifying the gap and then taking action to bridge that gap. It can be as simple as noticing a newcomer or somebody who might not belong to the home team in terms of their identification and learning that person's name and calling them by that name every day, when you see that person, you know, just really simple acts can can manifest inclusion.

Laura Kriska (38m 16s):

That then is duplicated by others. And, you know, it's really, it can be contagious.

Mark Graban (38m 23s):

Yeah. So I appreciate what you're doing Laura, to help spread that. I think, you know, if people want to become a wee builder, I definitely recommend checking out the book, The Business of We, written by our guest. Again, she is Laura Kriska. So Laura, thank you so much. This is, I really appreciate the, the, the, the fact that, that, that, that I can have you on the show and, you know, the, the experiences that you have, maybe we can do another episode in my lean podcast sometimes because there's this overlap where there's so much, I want to ask about your experiences in Japan, your experiences at Honda. Let's talk more about being a, we builder for a, for a different podcast audience sometime.

Mark Graban (39m 4s):

That'd be great. Thank you. Yeah. So thank you. Thank you so much for your story and for taking that mistake and building it into something really special. So thank you for it that Laura, thanks again. Well, again, I want to really think our guests, Laura Kriska for a link to her website and to her book. And for more information, you can go to MarkGraban.com/mistake61. If you like today's episode, if you liked the podcast in general, please share it with a friend or with a colleague or on social media that would really help us grow the show. And I hope this podcast inspires you to reflect on your own mistakes, how you can learn from them, or turn them into a positive I've had listeners tell me they've started being more open and honest about mistakes in their work.

Mark Graban (39m 52s):

And they're trying to create a workplace culture where it's safe to speak up about problems. Cause that leads to more improvement in better business results. If you have feedback or a story to share, you can email me myfavoritemistakepodcast@gmail.com. And again, our website is myfavoritemistakepodcast.com