Listen:

Check out all episodes on the My Favorite Mistake main page.

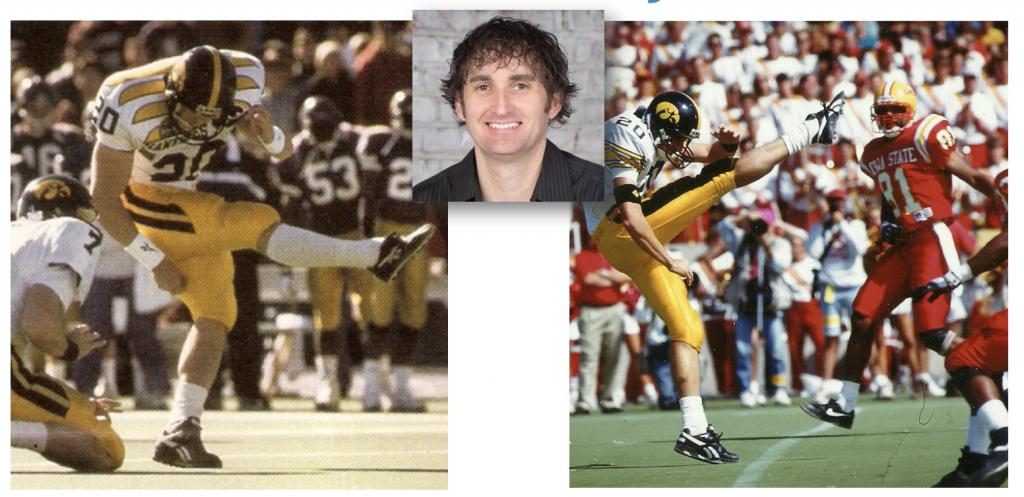

My guest for Episode #99 of the My Favorite Mistake podcast is Brion Hurley, a friend of mine from Lean Six Sigma professional circles, who I recently learned was an American football kicker and punter in college (Iowa Hawkeyes) and a number of professional teams (the NFL and Arena Football).

Brion is the founder of his company, Business Performance Improvement and he's a Lean Six Sigma Master Black Belt. He's the author of a free eBook called Lean Six Sigma for Good: How improvement experts can help people in need, and help improve the environment, and he's the host of two podcasts: Lean Six Sigma for Good and Lean Six Sigma Bursts.

In today's episode, Brion shares his “Favorite Mistake” story about the practice routines he developed as a kicker at the University of Iowa. Why was it a mistake to focus so much on practicing long field goals and how did that affect his performance in games? What was it like to lose his starting job? What did that teach Brion about mistakes in our careers?

Other topics and questions:

- Lessons from practicing wrong? Not evaluating the misses?

- What was your mindset on the pressure of a kick that might be seen live by 70,000 fans or more on TV?

- Game-winning kicks or opportunities?

- Hayden Fry story about Northwestern

- Referee mistakes?

- Social media age – criticism and threats toward kickers

- A blog post I wrote about fans blaming a college kicker

- How has this affected your view on workplace pressure now?

- Can we develop bad habits without a coach?

- Video of Brion's kicking highlights from Iowa

- Read a piece he wrote about his kicking mistakes

Scroll down to find:

- Watch the video

- How to subscribe

- Full transcript

Watch the Episode:

Quotes

!["The physical part [of kicking] is important, but the mental part is almost more important because you can get in your own head and you can start to think differently, and it changes how you behave and how you're performing."](https://www.markgraban.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Brion-Hurley-My-Favorite-Mistake-2.jpg)

Subscribe, Follow, Support, Rate, and Review!

Please follow, rate, and review via Apple Podcasts or Podchaser or your favorite app — that helps others find this content and you'll be sure to get future episodes as they are released weekly. You can also become a financial supporter of the show through Anchor.fm.

You can now sign up to get new episodes via email, to make sure you don't miss an episode.

This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network.

Other Ways to Subscribe or Follow — Apps & Email

Automated Transcript (Likely Contains Mistakes)

Mark Graban (1s):

Episode 99, Brion Hurley, former kicker in college and professional football, author of the book Lean Six Sigma for Good.

Brion Hurley (10s):

So when I look back at my playing days over the years, I think what stands out to me was my mistake around how I practiced

Mark Graban (22s):

I'm Mark Graban. This is my favorite mistake in this podcast. You'll hear business leaders and other really interesting people talking about their favorite mistakes, because we all make mistakes, but what matters is learning from our mistakes instead of repeating them over and over again. So this is the place for honest reflection and conversation, personal growth and professional success. Visit our website at myfavoritemistakepodcast.com. For show notes, links, and more including some highlight videos of Brion kicking, go to markgraban.com/mistake99. Thanks for listening. And now on with the show and the start of the college football season, our guest today is Brion Hurley.

Mark Graban (1m 8s):

We share in some ways professional background and in some ways we don't, but we'll explore that today. He has a company called Business Performance Improvement. He is a Lean Six Sigma master black belt. He's the host of two podcasts, one called Lean Six Sigma Bursts, and there's another called Lean Six Sigma for Good. And he's doing a book series of that same title, the first edition, the first, no, what's the, I made a mistake there. What's the word, Brion, before I welcome you formally?

Brion Hurley (1m 42s):

Volume.

Mark Graban (1m 42s):

The first volume is available and he's working on more Lean Six Sigma for Good. So we'll talk about that later, but the thing we're going to delve into first, I think is interesting is that Brion was a, a place kicker in a way, what we would just call football for a global audience, we'll call it American football. He was at the University of Iowa. He kicked in some preseason games for the New York Giants and he played a number of seasons in different Arena Football leagues. So at that, Brion, let me say welcome. Welcome to the podcast. How are you?.

Brion Hurley (2m 12s):

Great. Thanks Mark.

Mark Graban (2m 13s):

We'll jump right in it's the opening kickoff, if you will, Brion, looking back at everything you've done, what would you say is your favorite mistake?

Brion Hurley (2m 21s):

Yeah, this is something I don't talk too much about as my college days and playing football at the University of Iowa. So when I look back at my playing days over the years, I think what stands out to me was my mistake around how I practiced. And as you mentioned, that was a place kicker. And I also did some punting, but it's really where the place kicking that I had a lot of ups and downs. And I look back at the way I practiced in my, my kata, if you want to call it that from the lean terminology was flawed. And, and I think that led to a lot of that inconsistency

Mark Graban (3m 1s):

And kata, sorry to interrupt. But kata is a word that that could mean like routine

Brion Hurley (3m 7s):

Pertaining like practice routine that you go through every day. And with sports, that's very common. Most people have a practice routine. They follow, and I thought I had a good one. You know, there was some logic behind it, but I think that was part of the issue that I struggled with through my career. So w what I ended up doing was thinking that, you know, as I was developing and, and working out and trying to improve that the farther I could kick the football the better. And so I practiced a lot of long bagels. So I go back to as far back as I could physically kick it. And I, I figured if I made those kicks, then everything shorter than that would be a piece of cake, right.

Brion Hurley (3m 52s):

It's closer and it's easier. Right? And so I spent a lot of time kicking 50 to 55 yard field goals as my practice. And I would spend majority of the time, you know, I'd do a little warmup, but go straight to the long kicks, what happened. And so that, that thinking that this would lead to success in the short term and the short, shorter ticks did not pan out. I struggled. So I ended up my freshman year of college. I red shirted, which means you take a, a year off and you get kind of acclimated to academics, and then you still have four years of eligibility.

Mark Graban (4m 32s):

So, and you can still Practice in a red shirt year. You just don't play in the games. What the rules are the time.

Brion Hurley (4m 37s):

Yeah. You just don't play in a game. And most freshmen do that in football, because it's such a physical sport and other positions besides place kicker. It's a very physical sport and you need the extra year of weight training and adding on weight and all that. So most of the, I think one or two players on my class actually played that year, most red shirt. So that's pretty typical. So I worked out and I got better and ended up playing, but then would to end my second year, I ended up losing my job and that was due to inconsistencies. So I could make a really good kick.

Brion Hurley (5m 17s):

And then the next one, shank it, or miss it badly. And the shorter ranges of what, like 35. Yeah, 35,

Mark Graban (5m 27s):

I guess it's short to mid range for college kickers, right?

Brion Hurley (5m 32s):

Yeah. So most of the kicks take place inside 40 yards, but that's not where I was spending my time practicing. So it didn't translate. That's what happened. I was, you know, focused on so much on the long kicks that I didn't really study and think about when I missed them. I just thought, oh, I'll just miss it. I'll just try again. And I never really studied the perfecting that technique to be really, really consistent about that. So I think that was one problem I have. And so I ended up losing my job twice while I was at Iowa and got relegated to doing only long field goals for my last two years.

Brion Hurley (6m 13s):

So that was a really difficult experience to go through, but I still think it didn't sink in right away that it was my practice routine that was causing that. So looking back if I had to do it over again, I would have changed up my, my approach on how I practiced and gotten more consistent, which is the most important thing for a place kicker is to be consistent on the make-able kicks, not, you know, and it was, I did make some long kicks. It did work out at times, but not to the point where you're going to be the starting kicker on all the kicks.

Mark Graban (6m 50s):

I mean, so you had your routines that you developed. I'm curious, you know, because there are other, it's not like an NFL team where there's only one kicker on the roster at a time college teams have including walk-ons three, maybe four kickers, and you've got a special teams coach who may or may not be a kicking expert, like, so I know, and we might, might get into a little bit of Big 10 talk, you know, at Northwestern, my alma mater the special teams coach is the head coach who played linebacker. I don't know if he's ever kicked a football in his life. So I guess my question is like, how much is it a matter of figuring out yourself, learning from what the other kickers are doing?

Mark Graban (7m 31s):

Like how much do you compare notes and how much coaching were, were you getting?

Brion Hurley (7m 37s):

It's nice that you can do that. But it also is you can get into some bad habits too, that you don't know. So had some coaches that had a little bit of knowledge and some had zero very little knowledge, but that's very, very typical that most of the coaches don't have a lot of experience. They're not, it's not as prevalent as it is now that you actually have a kicking coach that your team provides.

Mark Graban (8m 1s):

And I mentioned, there's an interesting dynamic where your teammates, but you're competing for a job. As you mentioned, you kind of win the job, lose the job. You're, you're practicing the same set of uprights. I'm just trying to picture, think through the dynamic of you want to watch each other, but how much, how much cooperation and help is there?

Brion Hurley (8m 24s):

Yeah, my best friends are actually the other people. I was competing with my ex kicker and punter friends. So interestingly, we hung out so much that we became really close and formed a good bond, even though we were competing with each other for playing time. And I, at first, I didn't know how that was going to go because I hadn't in high school. There wasn't a lot of competition for the job, but it was interesting. It was very much individualized it's we all know we were competing against ourselves that if you know, it wasn't the other fault, it was our own fault. If we didn't do well enough, and we all had opportunities, it wasn't like someone was perfect and you could never beat them out.

Brion Hurley (9m 6s):

You had opportunities and you just didn't execute on that. So it worked out very strange that that was closest. Bonds are the people we competing against. Now, I wouldn't say that we shared tips or gave advice to each other, but definitely the other closest people on my team that I still think in contact with people though, who I lost my job to, or I beat them out for their job. And you would think that they would hold grudges or would there be animosity there, but it's not the case at the end. I think that goes to the, you know, how the personality types of everybody, but also the team environment that as long as we're winning and we're doing well, you know, no one wants to be the one that's to blame for mistakes or costing the games.

Brion Hurley (9m 59s):

So if the team's winning and if there was someone better that can do the job than you, and it helps the team win. And that's kind of the attitude that most people take. So that's pretty healthy.

Mark Graban (10m 9s):

Cause for comparison, I'm going to come back to the big 10 thing. Cause the funny small world almost connection cause Brion and I've known each other for a couple of years in professional circles. And then I learned that you had kicked at Iowa and it was the same years that I was a student. I was playing drums in the marching band at Northwestern. So for those four years that our teams played each other every year. You know, we were in the same approximate location. In fact, I was actually on the field once at Kinnick Stadium, but I was there as a visiting marching band member when you were on the roster. But when you were playing for Iowa, Northwestern was, was terrible those years.

Mark Graban (10m 50s):

We were winning maybe three games a year, Iowa. You had an expectation of going to a bowl game, maybe going to the Rose Bowl. So maybe that maybe helped with the competitive dynamic of well there's, there's, there's some benefit, even if you're not the starting kicker to let's say this bowl trip or the excitement of being on a winning team, it would be a mistake to undercut each other, I guess.

Brion Hurley (11m 11s):

Yeah, absolutely. And I think that's just like in business, I think there's a lot of commonality there with the leaders and the coaches and how they set the tone for that. And so I had a coach that I played for was Hayden Fry, and he's very well-known legendary coach. And that's how he operated was. And he had a lot of success doing it that way. So that carried through to the players. And so, and I think what happened at Northwestern was actually during my time when Northwestern pulled off, what I think was maybe the most unbelievable turnaround of any sports team, because it was, I remember growing up, it was a guaranteed win when I would play at Northwestern and scores of 50 to, you know, we're very common and to see them evolve over those couple of years.

Brion Hurley (11m 59s):

So the first two years we won and the second two years we lost and it ended up 20 some game losing streak at Northwestern. And it was the culture that Gary Barnett set up there was amazing. And I think it started that we will win and we all have an attitude that we were not going to lose. And on the other team, when you see that happen game after game, that keep pulling out victories, despite what looks like a loss, they're going to have, they gain competence around that and your opponent starts to think, oh, here it goes again. They're going to pull out another one. And the psychology around that is so critical in sports that it's, it's, the physical part is important, but the mental part is almost more important because you can get in your own head and you can start to think differently and it changes how you behave and how you're performing.

Brion Hurley (12m 50s):

And it's such an important part, but it's, it was, I, I was on the back on the bad side of that whole transformation and I saw it firsthand, but looking back, it was very impressive what happened there?

Mark Graban (13m 2s):

Yeah. Cause I graduated in June of 95 and it was the fall of 95 when Northwestern had their amazing Rose Bowl run and I don't have any close connections to them. I tried reaching out once to Coach Barnett to try to see if he would be a guest on this podcast. But I there's a story thinking back to Coach Fry and we talk about mistakes. I, this may have been, I don't know, a mistake on his part because it was one of those I'm sure, you know, blowout, victories and reportedly I wasn't there. So like reportedly, allegedly Coach Fry came to shake hands with Coach Barnett on the field after the game and said something to the effect of, I hope our boys didn't hurt your boys too bad or something like that.

Mark Graban (13m 47s):

Well, that really got under Gary Barnett's skin. And I think Pat Fitzgerald, our current coach who was a player on those teams like Iowa went from, from our perspective to being like, yeah, just one of the other schools that kicks our butts. Most of the time to being like this red letter hated rival. And, and, and to this day, like I think Northwestern gets up more for that Iowa game maybe because of some of that history. So I don't know

Brion Hurley (14m 17s):

That time, those, that rivalry has been very, even over the years, 95 through current day, those games are competitive and close most part. And yeah, I think Pat Fitzgerald being on that team and being part of that transformation and carrying that over into the, the attitude and culture and Northwestern has been part of that dramatic change. And yeah, so it definitely starts at the top and how people think and behave and it lines up nicely with all the work we do with, you know, continuous improvement and every day getting a little bit better than the day before. And, you know, yeah.

Brion Hurley (14m 58s):

So the, the tie in with business and sports is very close in my mind. Yeah.

Mark Graban (15m 3s):

So I want to come back to some of your thoughts on the lessons learned. I mean, I, as an observer watching the Northwestern football program, you could see that as a turnaround situation. And like my first job right out of college at General Motors was a losing team. It was the Northwestern Wildcats of the time, of building car engines. And we got a new plant manager, which is kind of the equivalent of a head coach. And I, and I saw it. So I've seen reinforced in different settings, a head coach who's had success somewhere else because Gary Barnett had been an assistant coach on a national championship team at Colorado. He knew what a winning culture was.

Mark Graban (15m 44s):

And when you bring in that type of leader, whether it's into a car plant or to a football locker room, it takes time because that culture change is, is not easy to say the least, but it's doable with the right kind of leadership. So I find that kind of a optimistic, hopeful thing for a lot of organizations, but I wanted to ask you Brion,

Brion Hurley (16m 5s):

I would add on that because when I grew up, I grew up in Iowa City where the University of Iowa is located and I was born in 74. So in 79, Hayden Gry was brought in to be the coach at Iowa, 23 years of losing program, a losing season at Iowa. And he had a different attitude and he had turned around a few other programs and he did the exact same thing in three years, they were in the Rose Bowl. And so as far as I was old enough to remember football, he was the coach there. And so he did a same thing 20 years earlier with his transformation at Iowa too.

Brion Hurley (16m 45s):

So, and it's, it started from the top and how he ran his program and how he delegated to his assistance. And he set the vision and just kept the attitude high with the players. And then he worked with his manager, he worked with his assistant coaches, that's where he spent most of his time developing the assistant coaches. So yeah, that's, it's, it's, it's interesting story to, to kind of grow up that way and then end up playing and seeing this, the turnaround that happened there too.

Mark Graban (17m 16s):

Yeah. I it's interesting. Yeah. I've thought of Hayden fry in Iowa with the end results. I didn't know the turnaround story I was born in 1973. I was a kid, you know, the, the big program where I grew up University of Michigan has been mostly dominant almost forever with a few bad stretches here and there that, that, that, that occur. So, yeah, Wisconsin at one point with Barry Alvarez was also a turnaround story, which is easy to forget.

Brion Hurley (17m 45s):

And he was the assistant coach at Iowa under Frye, and probably learned a lot from that turnaround and brought that to Wisconsin and, and their program is, I mean, I hate to talk about these other schools that irritate me, but the turnarounds that those programs is very impressive and what they've done in Wisconsin is amazing. So, and that goes to Barry Alvarez and his philosophy, but I'm sure he picked up some things being on Hayden fry staff.

Mark Graban (18m 13s):

So now I think there are jumped to the business connections. I've got another kicking question. I want to ask you, but there's, there's that turnaround. And then there's sustaining the improvement, which connects to the work that, that we do, where Gary Barnett, after bringing the Northwestern program to the Rose Bowl, they had another great season of the year after he stumbled a little bit for, for two seasons. Then he left and took the head coaching job back home in Colorado that I think was a really important inflection point for Northwestern, where it could have been like, well, those two years were a blip and now we've gone back to what our state in the football pecking order had always been, but they brought in another coach, Randy Walker, who had been successful at Miami of Ohio.

Mark Graban (19m 1s):

He then brought them back up to a sustained, like going to a bowl game was now kind of an expectation, not the rare event. And then when Pat Fitzgerald became head coach there, I'm fortunate as an alum and as a fan that there really was the step function improvement in the level of performance at Northwestern. And there there's risk and organizations we've seen in different types where let's say in a hospital, they make great improvement, new CEO comes and they go back to the old playbook and the Lean Six Sigma efforts or some of those results that are maybe more important can be temporary.

Mark Graban (19m 42s):

Know if you've seen similar situations in the business world.

Brion Hurley (19m 46s):

Yeah. I mean, I think that it becomes a, there was a, in my past work, I worked at aerospace company for 18 years and they started lean probably about two years before, one to two years before I started working there. And there was a big inflection point about your three or four where they said, I think we got this lean thing down. We can kind of delegate this back out to the departments. We don't need a central organization to manage this. And I think it was a really critical point. It didn't sustain CEO kind of realize that after about a year, another couple years and reinvigorated it again.

Brion Hurley (20m 32s):

And then I think it kind of maintained that level. So it did dip a little bit. I think they were premature to kind of claim success on their lean journey and think it was all embedded and ingrained in the culture yet. So it was a little early, but luckily they made a correction and got it back on track. And, and maybe that's a analogy back to like Michigan who is not doing as well as people are expecting to. And so maybe they're going to make a correction to try and get back onto the path that they want to be on. But it's, I think those inflection points are really important to be able to decide either we're going to stick with this, what we're currently doing, or we need to change, or we are going to get left behind, or a competition is going to beat us, or our competitors are going to continue to be us.

Brion Hurley (21m 23s):

So,

Mark Graban (21m 25s):

So while I've got you, I mean, I do want to ask another football question when it comes to kicking and the idea of, you know, pressure situations game-winning kicks. So, okay. Not against Northwestern, but in other games, you know, did you ever have the opportunity for, for a game winning kick make or miss? What, what happened? What, what did you learn from that?

Brion Hurley (21m 45s):

Yeah, so two attempts, first one was in high school. We were, I think we were down by a point or two and I was really excited. This is my junior year and we didn't attempt very many field goals. I kept waiting and hoping for those attempts, but this one was set up nicely for, for a check because we were down by one or two and time was running out and you almost had no choice, but to kick a field goal. So, and that kid got blocked and someone got through and cleanly blocked it. And there really wasn't a good shot at me getting the kickoff. So that was pretty disheartening. Cause you know, those things are really good for the resume and to get attention of schools.

Brion Hurley (22m 32s):

And so I was really selfishly looking for an opportunity to make a game winning field goal. So, you know, just trying to deal with it, you know, just, no, I guess I was frustrated with that, how it turned out like that, but I just kind of go back to say, is there anything I could've done differently? And I, I think everything I did was correct. And I thought I handled the pressure. Okay. I didn't feel super nervous. So I think I got up, I still took a good, positive away from it. Had I missed it and had been clean and maybe I would have reacted differently or how to deal with it a lot differently than that.

Mark Graban (23m 11s):

So what you're saying there, it's not like it wasn't a low kick. I mean, even though the kicker, you think of it as such an individual thing, there, there is a team effort there between the snap, the blocking the hold.

Brion Hurley (23m 24s):

Yup. That, that was one where you could say not, not your fault. Yeah. A field goal is really three key people. It's the snapper holder and the kicker itself and any one of those can cause problems for the others. Right. And so plus you have your eight other players blocking and trying to keep people out, which in that case didn't happen. But yeah, the, so yeah, so yeah, it wasn't a low check someone cleanly got through. And so I think I took away a positive because I didn't see that I could have done anything better or different in that situation, but it was a good experience to go through that for the first time. Yeah.

Mark Graban (24m 2s):

And then what was the other,

Brion Hurley (24m 4s):

I didn't have any attempts in college that were considered game winning or gain critical. There's a lot of misses that I had that I think were pivotal points of the game, but not like fourth quarter late in the game. So I took different things off of those misses. But later when I played arena football, it was the, we got a road game to San Jose. So we ended up going down and had a last minute field goal to win the game. And there's actually a little bit more time on the clock. And if you've ever been to Rina football game, that's plenty of time to score a couple of times if there's two seconds on the clock.

Brion Hurley (24m 47s):

Yeah. That's plenty of time for a touchdown or a couple of plays maybe. Right. So I think there's maybe still 20 seconds left. And so the other team got the ball and had a chance to try a field goal and they ended up missing the field goal at the end. So technically I had a game winning field goal, but also the other kicker missed theirs as well. I could have been the game winning field goal. So that was my only actual one that got off clean.

Mark Graban (25m 19s):

And, and so I think it's interesting. You're talking about thinking back to the work that we do now, you think about process and you talk about results. There could be times where you, as the kicker could have followed your process and done everything right. And maybe not get a good result. There could be maybe on the flip side where maybe there's something more fluky where like a kick is low and it would've been going left, but somebody tips it and now, and then of going through the uprights, maybe it doesn't happen as often, but

Brion Hurley (25m 47s):

Yeah, I've had a, a tipped PAT extra point go through. Maybe it would have, I don't know if I would have missed it necessarily, but yeah, some fluky things happen or hits the crossbar at the wrong angle and it bounces backwards or bounces in. There's some good videos. You can look at strange field goals that hippo, ghosts, goalposts, and crossbars and stuff. And that's never a good sound to hear as a kicker, are the ball hitting the across bar? Usually that's not a good result.

Mark Graban (26m 17s):

Well, here's a random question. So I remember one game when I was a student at Northwestern, any win was precious and there was a, a chance for a game when you feel goal, probably time expiring against Michigan state and the kicker Brian Leahy, who was related to Pat Leahy, who kicked in the NFL for quite a while, the kick went over the upright, it went over the goalpost. So it was just, it was so high. And then it becomes a judgment call of the referee's looking up the game. I don't think it was even televised there. Certainly wasn't going to be any instant replay and Northwestern fans to this day say that the ref blew the call.

Mark Graban (27m 0s):

And so I guess it kind of begs the question of like, why are the goalposts not taller to the point where that just wouldn't even be an issue?

Brion Hurley (27m 7s):

Yeah, I don't know. And in fact that game winning kick I had was over the top of the arena uprights. And so it could have been a judgment call. They could have said that that was too close to where we think the line would have extended. And that happened a lot in arena and it happens a lot in regular football, the ball. If you look at the path most, I'd say over half the kicks are over the uprights and so they need to go much higher up so that there's less ambiguity in the decisions about whether the ball actually went through the uprights or not. It's, it's, it's definitely a challenge. And I wish they would add on another 10 feet at least.

Mark Graban (27m 51s):

I mean, who cares about aesthetics? I mean, if you look at the foul poles at baseball games, I mean, those extend all the way up to the upper deck and a lot of cases you could eliminate some of that possibility of a referee mistake.

Brion Hurley (28m 2s):

Exactly. Maybe I needed to get a referee

Mark Graban (28m 4s):

On the podcast at some point, maybe a retired referee. I don't know if they would be willing to admit mistakes, but you know, I think of those pressure situations, you know, a couple of other athletes that I've interviewed you, you feel like if I make a mistake at work, I don't have 80,000 people seeing it in person yet alone. How many on TV? And I'm not getting ripped on social media. Yeah. So I was going to, I'm curious, you know, because you played in, in the mid nineties, what are your thoughts now of like, you know, kind of, it's going to be leading question, but the, the unfortunate situation where people are idiots on Twitter and are being abusive, if not threatening to a college kid who missed a Keck.

Brion Hurley (28m 45s):

Yeah. I mean, it was, like I said, I didn't have a, a game where it was clearly my fault we lost, so I didn't have to deal with that in the stadium or people I run into. That was the way you got feedback on stuff like that, that would yell out something. Right. And I've been booed by my own fans before. So that thickens the skin really quickly. And we have great fans, but at times I deserve to be booed. Right. So, and so you deal with that and that makes you tougher. And that gets you motivated to not make that, have that happen again. And that drives your practice and your desire to improve.

Brion Hurley (29m 24s):

So, but on the same side, I don't know how they can deal with that today. I mean, I, I think about what would happen, you know, if social media was around back then and anyone could say whatever they want to, to players, you know, it was bad enough on the field. And just knowing that it was going in the paper the next day, and that you have to watch the film on Monday and rewatch it over and over again, the mistakes you made dreaded that, and you just want to curl up and go to sleep and not see anybody. And hopefully that time passes by and they forget what happened. So it was, it was the most amazing experience.

Brion Hurley (30m 7s):

And it's also, it was like the most stressful experience I've ever been through. So everything pretty much fails pales in comparison to what I went through. Then business situations, I still get nervous about things, but I always think back to this is really not the same as, you know, being in front of 70,000 people and trying to perform. And they're all watching you and if you screw up, they're all gonna know it. So the business situations are much easier to deal with. So I think that that did help me a lot with dealing with pressure and learning how to relax and control and not get too excited or too down.

Brion Hurley (30m 51s):

So that was a great takeaway from playing sports. But yeah, that was tough. It was, I wouldn't change it, but I also, there are some things that were really difficult to go through.

Mark Graban (31m 3s):

Yeah. Well, I appreciate you sharing and reflecting on some of that. And, and, and again, I mean the, the kicker is one part of the puzzle. I blogged years ago, I had a chance to go to a Fiesta bowl game in Arizona. It was Stanford against Oklahoma State and the Stanford kicker missed a 35 yard kick at the under regulation. And then he missed a 43 yarder in overtime and they lost. And there was, you know, you know, a lot of just, you know, over the top criticism of the kicker. And then you read about what happened. The snap was a little bit offline.

Mark Graban (31m 44s):

The holder did his best to gather it in. And then I don't know if this is a thing like for those of us who just know from the movie Ace Ventura, when this laces out the laces were in. And like, so there are all these different factors that could have thrown off the kickers timing, the ball wasn't held properly, but yet the kicker gets blamed.

Brion Hurley (32m 3s):

Yep. And that's the, you know, that goes with the role, right? The job is the least physically demanding in terms of like, you're not getting, you're not tackling, people are being tackled, which everyone else has to deal with. So the perk is you don't have to go through all of that. But the other side of that is you take on all the glory, if you do well, and you take the blame. If you, if you mess up, they're not going to see the whole, their didn't do their job or the snapper, or some Lyman, let someone in and get their hand on it. That's, it's sometimes hard to tell what went wrong. Exactly. So that kind of comes with the territory. But yeah, you know, it's, I've had, I have friends that played in the NFL nine years and three of them had very high profile misses in playoff games and they received death threats multiple times from fans, you know?

Brion Hurley (32m 59s):

And so it's sad that that's where people take out their frustrations and do stuff like that. And now you're so wrapped up maybe in the sports that they would threaten people's lives over a game. So that that's disheartening that, you know, people are like that. And that was even kind of pre social media or is this kind of mid two thousands and stuff. And they all went through very difficult times just trying to recover from that because you know, their team didn't go to the super bowl or didn't go to the next round of the playoffs. And, and that also ended up getting in there, you know, probably hurting their chances of sticking around for another year and to see what they went through.

Brion Hurley (33m 40s):

It was like, I don't know if it was worth it that, you know, the money's good, but man, that's a lot to deal with. And it's almost like some post traumatic stress disorder. I don't want to try to equate it to stuff like that. But there is a lot of mental strain that gets put on, on people like that. And then to have that added on top where people are threatening their family and stuff, that's just uncalled for

Mark Graban (34m 5s):

Totally. And, and, you know, a fan is short for fanatic, but oh my gosh, don't, don't take it that far.

Brion Hurley (34m 13s):

I mean,

Mark Graban (34m 13s):

We'll be talking about the, the lack of physical action. You, you were relatively big for a kicker. So you, you were listed at six, four

Brion Hurley (34m 23s):

That's right. That was six, four. And like 215 when I ended up playing. So that's pretty tall for a kicker. We had some others in the league. John Hall was a kicker at Wisconsin. He was six, four. He was maybe 240, 250 or something. Our punter was 6, 4, 260. We had a strange batch of people that came through were larger than normal. But I think you're seeing the athleticism of the kicker position greatly improving over the last couple of decades where it's not just who is the soccer player that we can have them come out and they'll figure out how to play the football rules later.

Brion Hurley (35m 8s):

Just kick it through the uprights. It's now become very competitive. And some of the best athletes on the team are the kickers in some, on some teams. And some of them are world-class athletes that have just figured out that they're very good at this skill. So it's pretty, kind of been crazy to see the evolution of the kicking profession itself. When you can make millions of dollars a year, people are going to say, Hey, it's worth it. And I don't get banged up. And my knees aren't shot at when I'm 45 or 50. I got a lot of my teammates that would tell me when my kids get old enough, I'm going to call you and you're going to teach them how to kick. Cause they're not going to be alignment.

Mark Graban (35m 48s):

Is it, is it, is there a parallel to golf when you think of like practicing this kicking motion and a golf swing where I'm not a golfer, but there might be disadvantages for taller golfers because it's harder to maintain the consistency with longer limbs.

Brion Hurley (36m 5s):

Yep. It's it's the trade-off of consistency and distance. And so I was taller and I think that did help me kick the ball farther, but it also was part of the reason I was inconsistent with my, cause my technique, because it's, I guess there's more to kind of coordinate to get that repetitive motion down. Oh yeah. I think you'll see that with the golfers that they can drive it really far, but they struggle maybe on the short game, but the, the analogy of golfing is identical almost except for the, the ball is not stationary, except for like a kickoff and a field goal. There is a motion and people are rushing you. So if they could simulate that in the golf course, then it would be identical to a physical kick.

Brion Hurley (36m 48s):

But yeah, the mechanics are very similar. It's the practice often done by yourself focusing on it. You know, if I was to change the way I practiced, I would've kicked fewer balls. Each time I would have stopped after every kick and evaluated any mistakes or errors I made and maybe looked at was my placement off. Did I step it off incorrectly? Did I go too fast or too slow? Did my plant foot land in the correct spot each time? Instead, I would often just like, I was mad that I missed it and I line up and kick another one right away and I never stopped and studied what went wrong.

Brion Hurley (37m 30s):

And I think that kinda ties back to our discussion too, is we just want to move on to the next thing and we don't want to go back and revisit what, why things failed or didn't work out. Right. And I think I would have been much more, my improvement would have been faster and better had I studied those mistakes and learn from them instead of just trying to get out of my head and move on to the next kick.

Mark Graban (37m 57s):

Yeah. Again, it comes back to the process, not just the result and maybe looking for the root cause if you will, of, like you said, why did I miss that case? Yup.

Brion Hurley (38m 8s):

And is there a lot of, there's a lot of variables from how quickly you step back to your alignment. When you step back at the angle to how many steps you take over the pace at which you move towards the ball, your foot placement, and then even the ball and how it's angled and positioned by the holder. There's a lot of little variables in there that doesn't take more. I've, I've moved like half inches on some of those things and it's made a difference in my kickings. It doesn't take much to get off a little bit.

Mark Graban (38m 38s):

It's just one other football memory that comes back here and Northwestern's kicker at the time. And only if you've ever met him, Sam Valenzisi, he was a pretty good kicker, but he was maybe he was maybe five eight, but he was known for, he made a lot of tackles. So he wasn't a real big guy, but he was maybe a little bit nuts and he would run down and not be last line of defense tackle. But like he was really racing downfield with the head of steam. He wanted to make tackles. And then sadly, he wasn't able to play in the Rose Bowl game. He missed the last couple of games of that season and the Rose Bowl, because I think what happened was toward the end of the game against Wisconsin, there was a kickoff.

Mark Graban (39m 20s):

And I think it was, you know, it was a touchback. And I think there was just this excited mood of, of, of the team and the winning and that game. And he jumped up in the air to celebrate the touchback, not points, you know, for people that don't know football, they didn't score any points. It just means he kicked it out of the back of the end zone and the team couldn't return it. He jumped up to celebrate in, landed, landed wrong, and really screwed up his knee. Yep. Kind of the mistake of celebrating something. So maybe to your point, Brion of not getting too low, not getting too high could have helped him out there.

Brion Hurley (39m 54s):

I think it was Martin Gramatica did that too on a celebration. Right. And so, and partly is you have different size shoes, you have a regular shoe and then you have a kicking shoe and it's not meant for like running and sprinting and doing a lot of stuff other than kicking. So, so you, now you're an even a little bit, and then you're doing something you're not normally practicing doing, celebrating. And so, but I've seen that happen a lot that people have injured themselves and it's probably a little embarrassing for them to have that happen. But unfortunately that, you know, you have a great season, you do everything right. And then something like that ruins your, your end of year.

Mark Graban (40m 35s):

And again, it's one of those high visibility mistakes. If I make a huge mistake here. I would edit it out. I mean, I don't always edit out my mistakes.

Brion Hurley (40m 43s):

Yeah. It's a, this the highlight tape version of, of everything. Right. So I don't have all the mistakes and misses there. Yeah.

Mark Graban (40m 53s):

So maybe one other thing to drop back to something you said earlier, and then we'll add before wrapping up, you know, you talked earlier about, I'm paraphrasing, you kind of develop some bad habits without having a knowledgeable coach there's risk of that happening and the type of work that you or I do today. So I wondering if you could talk about the role of, you know, what's called the master black belt in Lean Six Sigma is the risk that people who are earlier in their learning and development, if they're having to figure it out on their own might also develop some bad habits without, without a coach.

Brion Hurley (41m 28s):

Yeah. I think that's applies for lots of things that, you know, you don't realize, maybe you don't realize you need the coach or the benefits that the coach can provide, or it seems expensive to hire a coach and you think that you'll get through it or figure it out or, and you don't realize what the struggle will be without it. And so until you go through it and then you look back and say, that would have been nice for me to have someone there that could have guided me or corrected it and saved me a lot of struggle and frustration and mental anguish, I guess, to, to go through it. So I think it's, it's difficult for people to recognize the need for the coach, but I think where we're really, you know, stands out is when you look at people who are the top of their game, who still have coaches, oh, you're Michael Jordan and LeBron James and tiger woods and, and Serena Williams, they all have coaches still.

Brion Hurley (42m 27s):

And yet they're the best in their sport at the time. Or, and so why wouldn't any of us also require coaches to help us do our job better? And I think that's, I don't know if it looks like it's a weakness or something, or that you can say that you did it all by yourself or there's some pride thing, but yeah, I think there's really, you know, I personally probably need more coaches and I'm not using enough coaches. So I think we can all look to, let's find someone who's already done that gone down the path and can guide us in a way that allows us to learn, but also not forces us because I have had kicking coaches and camps, I've gone to where they said, you will do it this exact way.

Brion Hurley (43m 13s):

And it didn't fit my body style or type. And I struggled with it and it messed up my performance. And I think that's not a good use of a coach where they tell you do it exactly like this. But instead say, here are the principles. Here are the important elements and key points and make sure that you hit those key points, how you get there can be left up to your own flexibility or preference or technique, but you have to have a common method of stepping off your steps. You have to have a consistent speed to the ball and you have to place your foot. And this other thing, everything else you could take like Paul injure of the bears with a very unorthodox style.

Brion Hurley (43m 56s):

But if you do those key elements correctly, you will be successful. And he was very noticeable. So I think, you know, focusing on what is a really important thing that the coach can do and not do it exactly or do it exactly like me, or do it exactly this way, because I think that will not be successful.

Mark Graban (44m 15s):

And there are people in our professional realm who tried coming about it that way also I'm the expert, I'm the, they might even use a word like sensei and they'll say, yeah, don't question me, just do it this way. I'm like that in different ways can hamper somebody's development or

Brion Hurley (44m 31s):

It might not be the exact template and this exact form. And it has to look like this and it's, you're taking away. I think the learning part of it or so they can develop and move past that coach. And I did a little bit of a kicking and punting con coaching later. I wasn't great at it. I don't think I was built for that, but the people I worked with, I tried to be very flexible and really just kind of hone in on, I'm not going to correct everything you do wrong. I'm just look for patterns in the thing I see repetitively done. I know you misstepped somewhere on there. I'm not, I don't have to point that out to you. You can see that, but where I see that you're not doing something repetitively, I'm going to maybe highlight those things.

Brion Hurley (45m 15s):

And so, but I tried to not say, you need to study my tape and try to replicate what I did. Exactly. That would have been a disaster for them.

Mark Graban (45m 24s):

Well, thank you, Brion, for sharing, you know, perspectives from, you know, this world that, that I don't know any, I don't know anything about, you know, place kicking and I'm sure it's, you know, interesting perspective to hear some of your recollections there. And thank you also for connecting it to things that we face in other workplaces. So as we wrap up again, I guess has been Brion Hurley, his podcasts are one Lean Six Sigma bursts. The second one is Lean Six Sigma for Good. There's a book of that same title in a nutshell, what is, what makes it Lean Six Sigma for Good? What kinds of things do you cover on that podcast?

Brion Hurley (46m 3s):

Yeah, so I started off focusing on environmental issues and applications of Lean andSsix Sigma to work on things like energy reduction and water reduction and solid waste. And then as I was doing a little bit more work in Portland with volunteering with nonprofits, I kind of lumped all of that type of activity into a broader Lean Six Sigma for Good umbrella, where it's just, you know, it's not so much focused on the businesses making more revenue or having better quarterly returns, but it's about are we really solving social issues and important issues that affect everybody that are then the meaningful problems that we need to resolve.

Brion Hurley (46m 47s):

And so anything that's kind of like nonprofit based government agency focused and then other applications where the company is trying to do reduce their carbon footprint or their, how much pollution they're generating those types of things that are, you know, I think are really important problems that we need these type of thinking and skills to help resolve some of those issues. So, so I'm just trying, yeah. Finding people who've done some work in government or nonprofit work and trying to share some of their stories and, and hopefully motivate other of those organizations to learn a little bit more about these process proven we're good.

Mark Graban (47m 28s):

Well, thank you. And I hope people will check that out. Lean Six Sigma for Good. And when it comes to coaching or at least kind of like peer coaching, Brion and I are both involved in a group that we call Lean Communicators, where we get together and we try to help and coach each other out in a kind of a, you know, informal, collaborative way. You can learn more about all of our podcasts leancommunicators.com. So Brion, thank you for being a guest. And I'm really glad we could do this today. Yeah. Thanks for having me. Well again, Brion Hurley for being our guest today and for show notes, links, and more again, you can go to markgraban.com/mistake99 as always.

Mark Graban (48m 8s):

I want to thank you for listening. I hope this podcast inspires you to reflect on your own mistakes, how you can learn from them or turn them into a positive I've had listeners tell me that they started being more open and honest about mistakes and their work. And they're trying to create a workplace culture where it's safe to speak up about problems because that leads to more improvement and better business results. If you have feedback or a story to share, you can email me myfavoritemistakepodcast@gmail.com. And again, our website is myfavoritemistake,podcast.com.